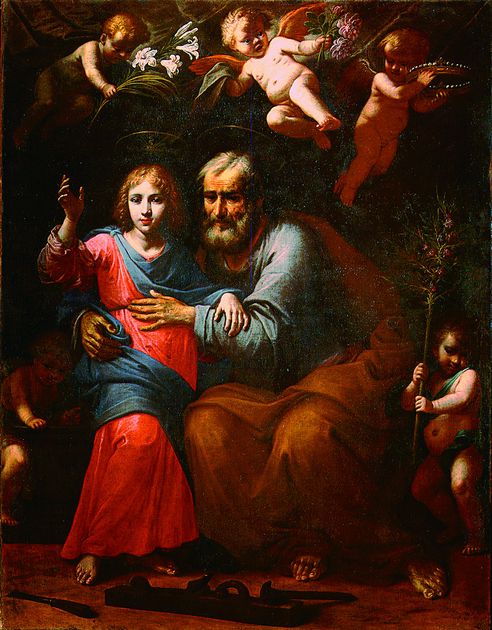

The 17th century had seen Naples transformed into an artistic epicentre after the huge success of the Caravaggesque school. Neapolitan influence continued in the following century thanks to the international enterprises of the Baroque master Luca Giordano and of other equally influential artists such as Nicola Malinconico. Malinconico was a sensitive, versatile painter who achieved an incomparable chromatic luminosity and compositional range at the peak of his career, as can be appreciated in the Good Samaritan. The extreme visual cleanness directs all attention onto the two protagonists: the injured figure, disarmed in his nakedness and exhibited almost in ecstasy in the beauty of his vulnerable body; the Samaritan, attentive and considerate, framed in his long, thick beard, restores a mild, reflective atmosphere after the violent action of the martyrdom. The wise healer is endowed with a slight dynamism, which can be seen in the sparkling reflexes on the arm he is medicating; the airiness of the new “atmospheric” painting now intervenes on its coloured hues.

The subject of the “Good Samaritan”, taken from St. Luke’s gospel, first became popular through Jusepe De Ribera and Caravaggesque tenebrism. The main interest was in the dramatic light contrasts and the intervention of the Samaritan who recovers and “saves” the victim of the attack from the sinister danger lurking around him. With Niccolò Malinconico this theatrical naturalism gives way to a balanced decorative taste whose “soothing” serenity is a foretaste of the agile, delicate 18th-century painting style.

This canvas is displayed next to other works of the Caravaggesque school, such as the Noli me tangere by Batistello, the Semiramis by Cecco Bravo and The Repudiation of Agar by Mattia Preti.